I was asked at a recent event if the colors we see in photos of celestial objects are real, and if any photos we see from space appear as they would to our eye. The first question centered on what are known as “false color” images and whether they accurately represent reality.

The electromagnetic (EM) spectrum is the range of wavelengths at which EM radiation, or light, is produced. What humans perceive as visible light is only a tiny slice of the EM spectrum. Our telescopes have observed the universe in a large portion of the EM spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays and everything in between. These observations have been crucial to our understanding of the universe, revealing truths that we would never have discovered otherwise.

To make use of the data obtained in wavelengths invisible to the human eye, we substitute one wavelength, or color, of light for another in images. We call images where we substitute one wavelength for another “false color” - a misleading term. True, the color of the image does not match the color of the source, but there is nothing false about the image itself.

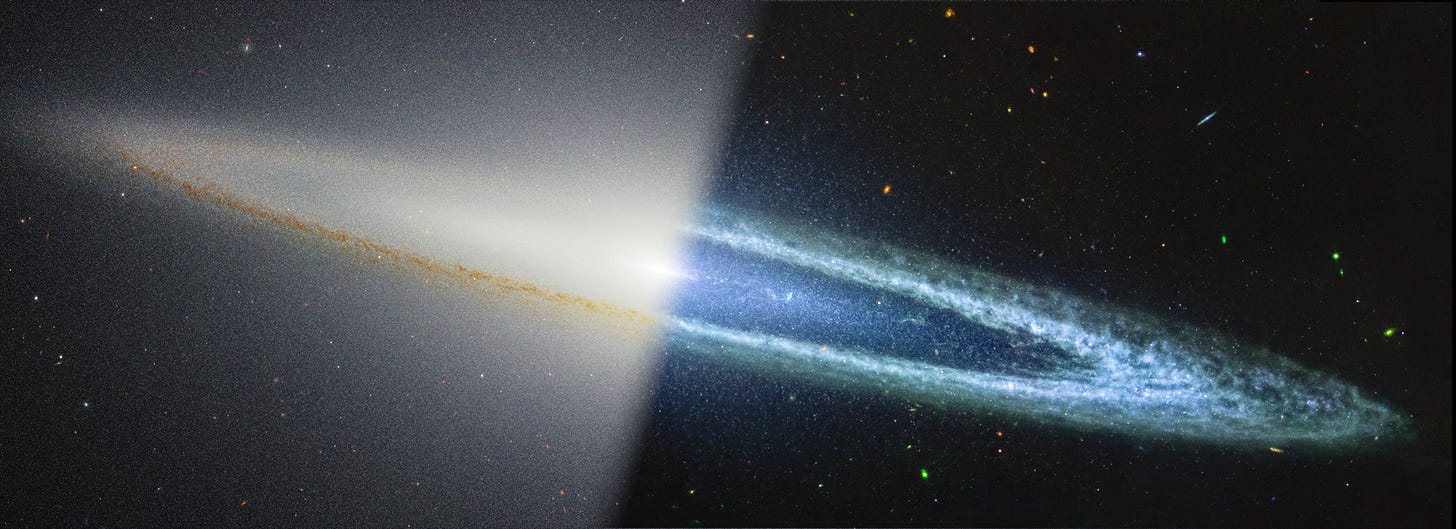

The Sombrero Galaxy, also known as M104, lies about 30 million light years away from us in the constellation Virgo and is easy to see in amateur telescopes. The galaxy, which is a little more massive than the Milky Way, was recently imaged by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The telescope’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument captured glowing stars and dust throughout the galaxy. The wavelengths captured by NIRCam are shown on the left of the photo.

An image obtained by JWST’s Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) in 2024 weaves a different sombrero. This image, represented in blue on the right-hand side of the photo, shows the clouds of gas and dust that are actively creating new stars in the galaxy’s outer disk. Observing multiple wavelengths reveals hidden structures and processes, allowing researchers to reach a deeper understanding of the history, evolution, and structure of a variety of celestial objects.

To see the invisible yourself, try this at home: Take the remote control for your TV and look at the part you point at the TV. Press some buttons and note what you see. Now open the photo app on your smartphone and repeat the experiment as you watch through the photo preview screen. Chances are, you’ll see a new flash of light coming from your remote. This is a false color image of your remote control’s infrared signal.

The second question was whether there were photos of celestial objects that accurately represent what we would see in natural light.

The answer is a resounding yes. Most photos you see of celestial objects are in visible light.

The Weekly Roundup.

The Morning Sky

Venus dazzles me almost every day, blazing brighter than any star low in the east before dawn. Saturn, shining a dull yellow to the upper right of Venus, will be visited by the waning (getting smaller) crescent Moon on the morning of the 19th.

The Evening Sky

Jupiter is gone for now, lost in the glare of the Sun. Mercury is low in the west after sunset, while Mars shines rusty red higher up the western sky as the Sun sets.

Dan Price is a NASA/JPL Solar System Ambassador and informal educator. Have a question about astronomy or space science? Send an email to dan@starpointestudio.com and it might be featured in a future column.

This is very useful for me to understand, and to be able to articulate. The question of 'artificial color' comes up so often in public outreach!